The physical and emotional changes of puberty reflect a biological transition from childhood to adolescence and young adulthood. In boys, these changes result from gradually increasing levels of testosterone, a hormone produced primarily by the testicles. The timing of puberty and this increase in testosterone varies widely between boys, however, it is important to be aware of situations where this timing reflects an underlying problem.

The testicles serve two main functions:

- they produce hormones that control puberty, sexual characteristics (facial hair, voice changes) and sexual function

- they contain sperm which are required for reproduction

Among boys treated for brain tumours, both functions have the potential to be impacted, either as the result of the tumour itself, or more commonly, as a result of treatment.

Therefore, monitoring a child’s progress through puberty is an important component of his medical follow-up after treatment for brain tumours.

What happens during puberty?

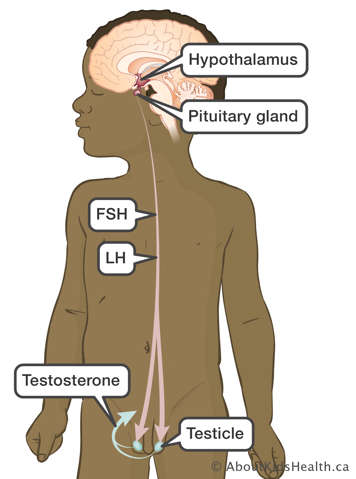

Puberty begins through a chain of events that start in the centre of the brain, in areas called the hypothalamus and pituitary gland. The hypothalamus produces gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH). This hormone then triggers the pituitary gland to produce two hormones called follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH). FSH and LH trigger the testicles to produce:

- Testosterone (the principal hormone needed for male puberty)

- Sperm

How are puberty and fertility affected by brain tumour and treatment in boys?

Treatment for a brain tumour, can impair hormone production. If GnRH, LH or FSH are not produced in the brain, then the testicles will not receive the instructions to produce testosterone and puberty may be delayed.

If only the hypothalamus is injured (either by the tumour, surgery or radiation), then puberty may come early. The hypothalamus is more sensitive to radiation than the pituitary gland.

If the cells that produce testosterone, Leydig cells, are damaged by chemotherapy, a boy may not be able to produce enough testosterone. As a result, he may not experience the physical changes of puberty at a typical age, or he may start puberty but fail to continue to progress through puberty at an expected pace.

The parts of the testicles that are involved in sperm production, the Sertoli cells and the seminiferous tubules can also be affected by alkylating chemotherapy. These effects can be harder to detect externally. The testicles may be smaller than would be typical for a boy of the same age and sperm production may be decreased or absent.

The production of sperm does not decrease significantly with aging. This contrasts with the availability of eggs, in women, which decreases as they become older and approach menopause.

Puberty

The timing of puberty onset is highly variable and may be influenced by many factors including family patterns and medical conditions. Boys may be “early bloomers” or “late bloomers” neither is necessarily a concern, although if pubertal timing is outside of the typical ages, it may require assessment by a clinician. Typically, puberty begins in boys with growth of the testicles beginning any time between 9 and 14 years. This is generally followed by the development of pubic hair, voice deepening and other physical changes.

- Boys treated for brain tumours may experience early puberty or late/absent puberty. The first sign of puberty in boys is the enlargement of the testicles, followed by enlargement of the penis and the development of pubic hair. If this occurs before age 9, it is considered early.

- The lack of enlargement of testicles and other pubertal changes by age 14, is considered delayed puberty.

Fertility

In addition to their role in producing hormones, the testicles contain sperm. Some chemotherapy drugs used in the treatment of brain tumours can impair the ability to produce sperm. As a result they may impair fertility--the ability to produce biological children.

Young men who were previously treated for brain tumours and who subsequently try to conceive, may experience difficulties in having a baby.

What causes problems with puberty and fertility?

Several factors affect puberty or fertility by causing damage to the organs and cells involved in the normal progression of puberty and reproduction:

- Children who have been diagnosed with germ cell tumours or a hypothalamic glioma may experience early puberty as a direct effect of the tumour. This is more common in children with neurofibromatosis (NF).

- Radiation therapy to parts of the brain called the hypothalamus and pituitary gland may affect the ability to produce hormones that are needed for puberty: GnRH, LH and FSH.

- Craniospinal radiation may have an impact when the radiation beam exits the body through the upper pelvis. In boys, the radiation beam may affect the testicles.

- Chemotherapy drugs, in particular, alkylating agents, may delay puberty and cause infertility. This category of drugs includes cyclophosphamide, ifosfamide, lomustine (CCNU), carmustine (BCNU), procarbazine and thiotepa.

How can problems with puberty and fertility be treated?

Monitoring

To monitor the function of the Leydig cells, routine visits will include a physical examination to evaluate puberty changes. This will include an examination of the testicles and may also include blood tests to assess the levels of testosterone and the pituitary hormones, FSH and LH.

The only way to know if sperm production has been impacted is by analyzing a semen sample. This may be an option for young men who wish to know whether they are producing sperm, or when they are interested in conceiving a child. A semen analysis can be arranged by the doctor or nurse practitioner.

Treatment for early (precocious) puberty

For early puberty, occasionally children may be offered treatment with medications to slow down puberty. Depending on their age, this may be suggested to prolong their period of growth, since once puberty has finished, a child typically stops growing shortly thereafter.

Children who experience early puberty may or may not benefit from pausing puberty. If the health-care team decides that a child would benefit from pausing puberty, a medication called leuprorelin can be given by injection to slow down a child’s progression into puberty. This treatment is usually continued until the typical age when puberty would begin.

Reasons to consider pausing puberty include:

- If the health-care team is concerned that going into early puberty will cause impaired final height (i.e., that your child will be shorter than they would have been without treatment). Typically, if children enter puberty before age 6, this is a possibility, and there is evidence that pausing puberty may lead to increases in final height as an adult. When puberty begins after age 6, the evidence is less clear and a decision to pause puberty will need to consider multiple factors related to the goals of treatment, including a child’s current height, their bone maturation and parents’ heights.

- Starting puberty significantly earlier than peers can be emotionally challenging for children and for their parents. Concern about emotional impacts of early puberty can be a reasonable reason to pause puberty.

Decisions about pausing puberty will be made with the input of a child, caregivers, the primary oncology team and an endocrinologist, a doctor who specializes in treating disorders of hormone production and timing.

Treatment for late (delayed) or absent puberty

If there are no signs of puberty by an age where it would typically be expected (14 years in boys) or if puberty starts but then fails to continue, this is referred to as delayed/absent puberty.

For young men with absent or delayed puberty after brain tumour treatment, this may be due to effects of the treatment on the testicles. It may also reflect damage to the pituitary gland in the brain, which is responsible for sending signals (called LH and FSH) to activate the testicles. Regardless of the cause, the treatment is the same.

Treatment with hormones (testosterone) may be recommended to promote the physical and mental changes of puberty.

Testosterone is given by injection every 4 weeks. In addition to the external changes influenced by testosterone (hair growth, voice deepening, enlargement of the penis, muscle growth etc.), it also influences bone strength, heart health and brain development.

Testosterone is initially given in small doses and this dose is increased gradually over a period of 2-3 years to mimic the pattern seen in children who undergo puberty spontaneously. This approach helps allow the child’s body to change gradually and to achieve the most natural final appearance of the adult body.

Treatment for infertility

The treatment required for children with brain tumours may impact the ability to make sperm. Teenage boys with cancer have the opportunity to freeze sperm, also called "sperm banking", for possible use later in life. With this approach, a semen sample is collected from the teen ideally soon after the cancer diagnosis, and before starting anti-cancer treatment. The semen contains sperm and is stored in a special freezer until the young man would like to use it. Studies have shown that teens who have not been offered this opportunity may feel disappointed and regretful about it in later life.

It is important to consider sperm banking among teen boys newly diagnosed with brain tumours. There are, however, several potential barriers to overcome. When introducing this idea to the teen and his family, there are a number of considerations, including:

- presenting the option to teenage boys in a mature and sensitive manner, without causing embarrassment

- when to introduce the idea, especially if the cancer is life-threatening and needs immediate treatment

- addressing ethical issues related to sperm banking, such as what role the parents/caregivers should play in the teen’s decision making

- how the semen sample is collected, recognizing that some cultures and religions may oppose the use of masturbation to collect the sample

- whether alternative to masturbation may be an option, such as a procedure called electro-ejaculation, which can be performed when a young man is undergoing anesthesia

- what will happen with the sperm sample if the person dies before the sample is used

These are considerations that the teenager, in discussion with his family, and his health-care team will need to address if the teenager wishes to preserve his sperm for future use. If sperm banking is of interest, please speak with the oncology team to learn more details.

Sometimes, the cancer treatments do not leave any surviving sperm. In such situations, a young man will be unable to conceive a biological child. With new surgical techniques, some young men may be able to retrieve sperm even when the semen analysis is abnormal. This procedure, however, may have risks of genetic changes resulting from the chemotherapy, therefore freezing semen before starting chemotherapy is the strategy of choice whenever feasible.

How will this affect your child’s future?

Children with early puberty may be shorter than they would have been without cancer treatment.

Teenagers with delayed or absent puberty may need to start hormone therapy to continue through puberty and may need to remain on hormone therapy for life. In addition to maintaining sexual characteristics and sexual function, testosterone is important to maintain bone strength and heart health.

Young men who have been treated for cancer, may have trouble conceiving a child or be unable to conceive a child, as the result of decreased or absent sperm. Even if a child has had normal puberty, he may not have normal sperm production. However, there are many ways to build a family, including use of donor sperm and adoption. These are options that a young man’s care team, potentially with the input of a fertility specialist, can discuss when they feel the time is right.

Children's Oncology Group Long-Term Follow-Up Guidelines: Precocious Puberty after Cancer Treatment

Children's Oncology Group Long-Term Follow-Up Guidelines: Male Health Issues after Cancer Treatment