Fine motor skills are the control of small muscles in the fingers for grasping and manipulation. Typically, these skills are coordinated with or in response to visual input. In other words, vision and movement work in concert to produce actions. The term “visuomotor skills” is often used to describe this process.

Visuomotor skills begin development in infancy, and continue to develop through the toddler and preschool years. These are the skills that eventually allow a child to perform many routine tasks like buttoning shirts, tying shoelaces, and eating with utensils. They also support printing and writing, artistic expression such as sculpting in clay, drawing, and painting, and playing musical instruments. What begins as a toddler’s scribbling progresses to drawing of shapes, then drawings that represent real or imagined things such as animals and funny monsters. As a child progresses from kindergarten through the primary grades, initial large, ill-formed printing progresses to well-formed, smaller, and more evenly spaced characters.

Some of the complications of premature birth can affect development of visuomotor skills. Many studies have reported visuomotor deficits in children who were high-risk premature babies compared to healthy children born at full-term. Fortunately, there is much that a parent can do to help enhance their child’s visuomotor development.

Stability and coordination

For visuomotor skills to develop, a child must have reached certain milestones in terms of growth and control of movements. For example, a toddler will learn to keep themselves steady before they master moving around. Additionally, a child must have some control and stability of the body before they can control their shoulders and arms. Typically, this process begins with the child learning to control the centre, or proximal, parts of the body such as the trunk, and progressing to control of the outer, or distal parts, of the body such as the finger tips.

Each joint must be stabilized before it can be used for refined movement. For example, the toddler holds their elbow steady when using their shoulder to guide a paint brush; a four-year-old holds their fingers steady while learning to control colouring movements from their wrist.

New movements are large at first, often with overflow, and then become refined with practice. For example, when learning to use scissors, a child will often open and close the opposite hand and mouth as they try to cut.

Handedness and pencil grip

Babies, toddlers, and preschoolers need to develop manipulative skills in both hands so that both hands are functional for two-handed tasks. Usually before a child is four years old, they will have gradually established what is called a hand preference, which is the preferred use of one hand over the other. This becomes firmly established as a dominance by age six; at this point, the child will be left-handed or right-handed. Lack of hand preference by four years of age usually is a sign that fine motor skills are delayed in development.

As the child develops handedness and dexterity using one hand only, the way in which they hold their pencil evolves and become more refined, allowing for more control and precision.

Vision and control

Visuomotor integration is dependent upon efficient control of eye movements, adequate vision, and the ability to plan the motor act and carry out the required motor skill.

When learning new motor skills, the child must concentrate all of their effort on the activity and use vision to guide their efforts. As the skill becomes “automatic,” vision is no longer needed to guide a motor behaviour such as learning to print.

Developmental stages: two to three years

Stability and coordination

- The child can stabilize their body and shoulders during hand activities.

- They will try to stabilize their forearm when sitting at a table.

- They can paint at an easel, but has trouble colouring within the lines.

- They will mirror actions in the opposite hand during new or difficult motor tasks like cutting with scissors

Pencil grip and dominance

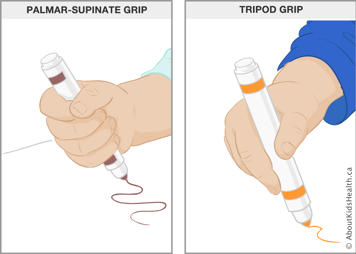

The child’s grip changes from "palmar-supinate" where all fingers grasp the pencil in the direction of the tip, to "tripod", where the thumb and index finger grasp the pencil in the direction of the tip and the pencil rests between the thumb and index finger.

There is frequent switching of hands. The role of the "helper" or nondominant hand emerges.

Visuomotor integration

- The child can identify circles, squares, and triangles.

- He can draw vertical and horizontal lines.

- By three years of age, they can draw lines and circles by imitation, and can trace a cross and a square.

Developmental stages: three to four years

Stability and coordination

- The child’s trunk and shoulders are stabilized during fine motor activities; the shoulders and elbows provide refined control. Good wrist control is developing.

- Colouring improves.

- Mouth and mirroring movements are still observed.

Pencil grip and dominance

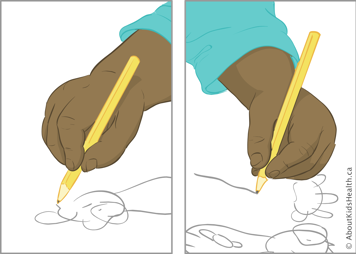

The child now uses the static tripod grasp (thumb, index, and middle fingers hold the pencil; hand moves as a unit).

There is frequent switching of hands. Use of the “helper” or non-dominant hand to stabilize and position work improves.

Visual-motor integration

- The child can copy circles, vertical, and horizontal lines from a model.

- He uses these shapes to draw pictures and copy words.

- He can copy simple block designs of three or four blocks.

Developmental stages: four to five years

Stability and coordination

- The wrist now provides some stability for controlled movements of the forearm and hand.

- The child can colour within the lines but may have some trouble forming letters.

- Mirroring movements have disappeared, but “overflow” movements, such as a tongue sticking out during cutting, still occur.

Pencil grip and dominance

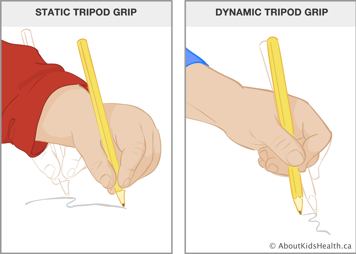

- The child’s grip varies between static tripod grip where the hand moves as a unit, and dynamic tripod grip in which small finger movements more finely control the pencil.

- Fingers are used to alter grip rather than using the other hand.

- Preferred hand is used predominantly.

Visuomotor integration

- Vision guides the hand when completing mazes.

- Letters are recognized, but may be “drawn” instead of printed (using proper letter formation).

- Some children print certain letters from memory.

Developmental stages: five to six years

Stability and coordination

- The child easily adjusts the posture of their trunk, arm, wrist, and fingers as needed for the task. Movements are efficient, finger dexterity is good, and many skills are automatic and are no longer visually guided.

- Printing skills improve, letters become smaller, and the child no longer has to copy from a model.

Pencil grip and dominance

- The child uses a dynamic tripod grip. The pencil is held near the tip. Finger movements guide small formations in printing.

- Dominance is firmly established.

Visuomotor integration

- The child copies diagonal lines and integrates them into triangles and diamonds.

- Printing becomes automatic by the end of kindergarten.

- The child does not need a model for reference when printing.

- The child can copy designs made from at least six blocks.