Acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) can develop because of gene changes inside leukemic stem cells. These changes can include chromosome translocations or changes in the number of chromosomes.

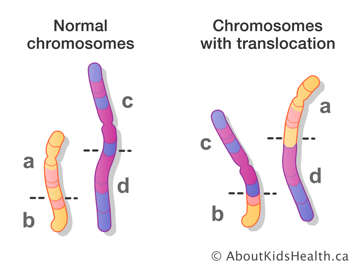

Chromosome translocations

Inside leukemic cells, a part of a chromosome can separate itself and attach to other unrelated chromosomes, producing new chromosomes that express genes in different ways. When chromosomes spontaneously rearrange themselves this way, it is called a translocation.

Problems arise when the translocation produces a new gene that instructs the cell to do things it normally would not — for instance, tell the cell to divide uncontrollably. For ALL, many translocations are more commonly found in different age groups. In a healthy cell, there are normally 46 copies of chromosomes; two copies of each. Every pair is numbered 1 through 23.

Translocation of chromosome 4 and 11 typically occurs in up to 80% of ALL cases of infants younger than one year old. The gene that is involved in this translocation is called the MLL gene. This is a subtype of ALL called Infant ALL.

The most frequent translocation that occurs inside leukemic cells in children 2–9 years of age is when parts of chromosome 12 and 21 fuse together. This is called ETV6-RUNX1 fusion (previously known as TEL-AML1). This translocation represents about 20% to 25% of all childhood ALL cases and is associated with precursor B-cell ALL, which is when there are too many B-cell lymphoblasts (immature white blood cells) in the blood and bone marrow.

The presence of this translocation is generally associated with a more favorable prognosis.

It is possible to find leukemic cells with chromosome 9 and 22 translocated. This is also called a Philadelphia (Ph)-chromosome-positive ALL and represents from 3% to 5% of childhood ALL. It is more common in children older than 10 years with precursor B-cell ALL. Special medications treat this type of ALL, which is considered high-risk.

Several other translocations may be present in your child’s leukemia. These should be discussed with your child's oncologist.

Changes in the number of chromosomes

Some leukemic cells have too few or too many chromosomes.

Too many chromosomes

About 20% to 25% of children with precursor-B ALL have more than 50 copies of chromosomes per cell. Typically, there are more copies of chromosomes 4, 10 and 17 inside the leukemic cell. A cell that has too many copies of chromosomes is called hyperdiploid. Children with hyperdiploid cancer cells generally have a good prognosis, as they respond very well to chemotherapy.

Too few chromosomes

In approximately 5% of cases, leukemic cells have too few chromosomes. A cell that has less than 44 copies is called hypodiploid cell. The prognosis is not as optimistic as in hyperdiploid.

In very few cases of ALL, leukemic cells can be "near-haploid," which means they have 24–29 copies of chromosomes. Although this indicates a very poor prognosis, it is very, very rare.