We would like to acknowledge the TB survivors who assisted in the development of this article.

Download a one-page summary about tuberculosis.

What is tuberculosis (TB) disease?

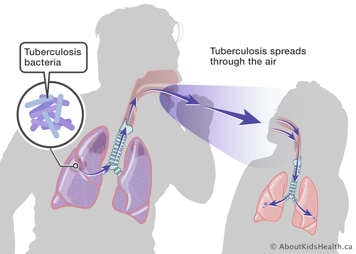

TB is caused by the bacterium Mycobacteria tuberculosis. When it causes symptoms, it is referred to as TB disease and can be infectious to others. TB is spread through the air by breathing in bacteria coughed out by infectious people. Children with TB are much less infectious than adults because their coughs are not as forceful.

In 2019, the World Health Organization estimated there were approximately 1.2 million children with TB worldwide.

TB disease requires urgent treatment with antibiotics to improve symptoms, prevent spread and cure the infection. Children who complete treatment usually no longer have symptoms and go on to live long healthy lives.

What symptoms does TB cause?

Most people with TB disease have symptoms. Symptoms can be general and affect the whole body:

- fever

- weight loss

- poor weight gain ("failure to thrive")

- night sweats

Or symptoms can depend on what part of the body is infected:

- lungs: cough; coughing up sputum (phlegm), which may become bloody; shortness of breath; chest pain

- lymph nodes: swollen bumps most often on the neck, which may drain pus

- abdomen (belly): belly pain, low appetite, nausea and vomiting

- brain: headache, confusion, seizures

- spine: back pain, weakness in the arms or legs

Symptoms can be different depending on the age of the child:

- Infants are more likely to have general symptoms such as poor feeding and difficulty gaining weight.

- Younger children under 5 years old are more likely to have severe forms of TB, including TB that affects the brain.

- Older children and adolescents have more usual symptoms such as cough that does not go away, fever, weight loss and night sweats.

Who is at risk for TB?

Certain groups are at higher risk for getting TB and developing symptoms. These include:

- People exposed to an adult or adolescent with infectious TB disease. This is the most important risk factor.

- Children born in a country where TB is more common. This includes many countries in Asia, Africa and South America.

- Children whose parents were born in a country where TB is more common.

- Children of Indigenous descent due to the harmful effects of colonization (including residential schools) and other social factors.

- Children with weakened immune systems due to certain illnesses (e.g., cancer, transplant, kidney failure) and medications (e.g., chemotherapy, steroids, biologics) are more likely to get TB disease if they are infected.

- People living in over-crowded housing with poor ventilation.

How is TB diagnosed?

TB is diagnosed by collecting a sample and looking at the bacteria under a microscope or growing it in the lab so that there are more bacteria to test. This is called a bacterial culture test. Samples can be taken from different body sites, but a sample from sputum (phlegm), stomach contents or fluid from a lymph node are most often used.

Diagnosing TB can be challenging, especially in younger children. This is because younger children have fewer TB bacteria present and are not always able to provide a good sputum sample for testing. If your health-care provider suspects your child has TB, your child might be admitted to the hospital for the health-care team to collect samples. Your child might have a tube placed in their nose to their stomach, called a nasogastric or NG tube. It will help to collect sputum that your child may have swallowed if they cannot cough up a sample on their own. This is often done on three consecutive days to improve the chances of detecting TB bacteria. Your child may have other tests or procedures, including for TB at other sites of the body, based on your child's symptoms.

Sometimes, TB is diagnosed even when test results are negative. This can happen when your health-care provider thinks TB is likely based on your child's symptoms, whether or not they have been in contact with someone with TB, or even when they have no symptoms if they have an abnormal X-ray or abnormal results on other tests.

Other tests may be done to support a diagnosis of TB. These tests can tell whether your child's body has been exposed to TB in the past but cannot confirm that it is making them sick now. These other tests include:

- the TB skin test (TST), where a small amount of killed TB-like protein is placed under to the skin to assess for a reaction

- a blood test called an interferon gamma release assay (IGRA)

How is TB disease treated?

TB disease is treated with a course of multiple specialized antibiotics taken by mouth over many months.

TB in the lungs or lymph nodes requires at least six months of treatment. If TB is in the brain, bone or multiple sites, treatment is often required for 12 months or longer. Your child may feel better quickly after starting treatment, but it is important that they keep taking their medications until their health-care provider says to stop. Otherwise, there is a chance of the TB coming back.

Multiple antibiotics are required to quickly improve symptoms and prevent spread to others, as well as to prevent drug resistance. Antibiotics are chosen based on the strain of TB your child has, but most people are started on four antibiotics: isoniazid, rifampin, pyrazinamide and ethambutol. These medications have been used for a long time, are generally safe and work well with less side effects than other medications. There are sometimes mild and severe side effects, such as vomiting during treatment—see the section, "When to see a health-care provider when your child has been diagnosed with TB" for more information.

How is TB prevented?

The best way to prevent TB in children is for adults and adolescents with TB to be quickly diagnosed and treated, as most children with TB get the infection from adults and adolescents living with them.

Before people exposed to TB develop TB disease, they often have the bacteria in their body without any signs or symptoms. This is a condition called latent TB infection (LTBI) and is detected by a tuberculin skin test (TST) or blood tests called interferon gamma release arrays (IGRAs). People with LTBI are not infectious to others. LTBI is easy to treat, and detecting it is one of the best ways to prevent TB disease from occurring.

Certain countries where TB is more common give the Bacille Calmette-Guerin (BCG) vaccine to infants to prevent severe forms of TB in young children. This vaccine is not given in most parts of Canada, except for certain areas in the territories where TB is more common. This vaccine is not given to older children or to people who have already developed TB disease.

Are there complications of TB disease?

Most children who are diagnosed quickly and take their full treatment will not have significant complications. Complications are more likely if diagnosis is delayed, if the bacteria has spread to multiple parts of the body or if the bacteria is resistant to treatment (when the regular medications do not work on the bacteria and new medications need to be tried).

Sometimes, a child's symptoms might temporarily get worse before they get better after starting treatment. This occurs in about 1 in 10 children and usually means the medicine is working to kill the bacteria, and your child's immune system is responding.

For some people treated for severe lung TB, studies have shown that they may have reduced lung function in the future. However, it is not known if this has a real impact on their lives, and it does not apply to most children who have mild TB disease.

If TB affects the brain or spinal cord, long-term consequences are possible. They may include cognitive difficulties, mental health challenges, weakness or difficulty walking.

How can I support my child with TB once they are home?

Due to a number of medications required to treat TB, many children need their caregiver's help to take their medicine each day. If your child does not like the taste of their medications, your health-care provider may be able to suggest foods you can mix with the medications to improve taste. Reward systems, such as a sticker chart, can also be a useful tool to encourage your child to take their medication.

Your public health team will also help support your child's treatment at home through directly observed therapy. This is where a member of the team visits your home to provide support and advice on how to manage the medications and appointments, watch for side effects and answer your questions and concerns. Directly observed therapy is the standard of care in TB treatment because it is associated with improved outcomes, greater treatment completion and a lower risk of TB coming back.

It is important to be mindful of the mental and emotional impact a diagnosis of TB can have on a child. A child may feel different than their peers or be excluded from different activities in their community, even after their period of isolation has passed. You can help by encouraging your child to talk openly about their emotions with trusted adults and using simple child-friendly language to talk about TB. (For example, "It's time to take your medicines for the germs in your lungs. The medicines will make you strong and healthy.")

What is next after my child is diagnosed with TB?

Some children with TB disease are not infectious to others. After treatment is started, those children and adolescents who could infect others may need to stay isolated at home until their public health team determines they are no longer infectious. During this time, children are not able to attend school in person, spend time with friends or take part in activities outside the home.

Your child will be followed by a team of health-care providers in a specialized clinic while they are on treatment, and beyond. This will include appointments to check in on symptoms and medications, repeat tests and answer any questions or concerns you may have.

When to see a health-care provider when your child has been diagnosed with TB

Please note that rifampin causes tears and urine to turn an orange/red colour. This is NORMAL and not cause for concern.

Several TB drugs can cause liver inflammation. Stop your child's TB medications and contact their health-care provider immediately if your child experiences:

- low appetite

- vomiting

- abdominal pain

- jaundice (yellowing of the skin or eyes)

- extreme tiredness

Call 911 or go to the nearest Emergency Department immediately if your child:

- has difficulty breathing

- is difficult to wake up

- has persistent vomiting

- has a seizure

At SickKids

The Tuberculosis Clinic is located in Clinic 7 on the main floor to the left of Shoppers Drug Mart. The clinic includes nurse practitioners, physicians, nurses, a social worker and public health professionals with experience in TB management and care.

Resources

Please see the following for more information:

- Toronto Public Health (TPH): https://www.toronto.ca/community-people/health-wellness-care/health-programs-advice/tuberculosis-tb/tuberculosis-tb-in-children/

- United States Center for Disease Control (CDC) and Prevention: https://www.cdc.gov/tb/about/children.html?CDC_AAref_Val=https://www.cdc.gov/tb/topic/populations/tbinchildren/default.htm

- World Health Organization (WHO): https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/tuberculosis

- Kids New to Canada: https://kidsnewtocanada.ca/conditions/tuberculosis

- British Columbia Centre for Disease Control (BCCDC): http://www.bccdc.ca/health-info/diseases-conditions/tuberculosis

- American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP): https://www.healthychildren.org/English/health-issues/conditions/chest-lungs/Pages/Tuberculosis.aspx

References

Lew, Y. L., Tan, A. F., Yerkovich, S. T., Yeo, T. W., Chang, A. B., & Lowbridge, C. P. (2024). Pulmonary function outcomes after tuberculosis treatment in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Archives of disease in childhood, 109(3), 188–194. https://doi.org/10.1136/archdischild-2023-326151